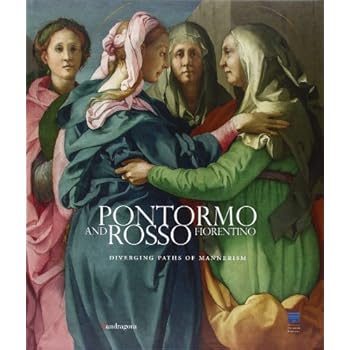

Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,History & Criticism

Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism Details

Review Where do you go after perfection?...In Florence, Jacopo Pontormo turned into a painter so arrestingly peculiar that art historians are stumped by him to this day. (Rachel Spence Financial Times, March 14, 2014) Read more

Reviews

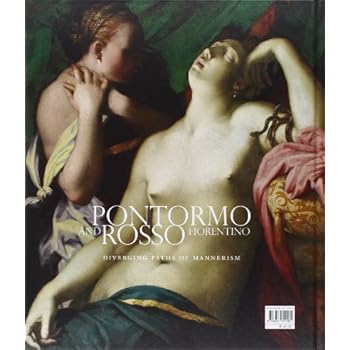

This is the catalogue accompanying the exhibition of the same name at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence from March to July 2014. The editors, Carlo Falciani and Antonio Natali, also curated the exhibition and are among the most highly respected scholars of the Florentine Renaissance who have published extensively on both Pontormo and Rosso. This is quite a large and comprehensive show, apparently the first one of such scope in almost sixty years, and it has drawn on over forty lenders internationally. According to the editors, the avowed purpose of the project was to reevaluate a number of things in the light of sixty years of research and scholarship: first of all, the notion of "Mannerism" itself, and then the painters' positions with respect to the political and theological issues of their time and the influence such positions had on their artistic choices. Such reevaluations have been made necessary by refinements in related fields, such as the recognition that Savonarolan sympathies were far more persistent in sixteenth-century Florence than had been believed, and the reassessment of the institutional crisis in the Roman Church, its effects on the political and theological situation in Florence and the influence of that situation on Rosso's rebelliousness and Pontormo's religiosity, etc. The final result of such reconsideration seems to be that the tendency of previous art history to lump the two together as a "pair" of rather rebarbative upstarts comprising a kind of "twinned" assault on Florentine traditions is not tenable. Instead, a new picture emerges: had the two not been born in the same year (1494) and just a few miles from each other, and had they not had a similar initial training in the "school of San Marco" (Pontormo under Albertinelli and Rosso under Fra Bartolomeo) and then in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto, there probably never would have been much of a compelling reason to consider them together in the first place. Even as teenagers working together, there was enough difference between them in style and manner from the very beginning that the editors can say they were "twins, yes, but non-identical" (15); if there is one general conclusion from all the discussion, it would be that the artists were not really culturally very related or stylistically very similar. Thus, the emphasis of the examination is on the "diverging paths" of the subtitle. This differentiation is well documented by the exhibits and the scholarly essays and commentaries that accompany them. The organization is generally chronological and thematic and is arranged in ten sections, treating the artists sometimes together and sometimes individually. The first section treats their youthful work (in fact, they started so young one could almost call it their "childhood work") in the Chiostrino dell'Annunziata and in Andrea's workshop and they are subsequently followed on their paths: Rosso journeying to various sites in Italy and then finally to Rome and the French court at Fontainebleau, and Pontormo staying for the most part in Florence during the politically turbulent Medici years. Intermixed are particular sections devoted to their portraits and their drawings, to Albrecht Dürer's important influence on Pontormo, to the establishment of the Florentine style of drawing and its influence on them, etc. Some more specialized investigations include the application of Vasari's categories of "prontezza" to Pontormo's work and of "fierezza" to Rosso in his second Florentine period, and there is a final section by Elizabeth Cropper dealing with the origins of the terms "maniera" and "manierismo" and their development and application, primarily in the twentieth century, by such writers as Walter Friedlaender, Paola Barocchi, Roberto Longhi, Craig Smyth and others.Altogether there are sixteen essays by leading scholars in their fields, including, apart from the editors, Philippe Costamagna, Tommaso Mozatti et. al.; they are completely authoritative and up-to-the-minute in their scholarship, and there is a huge amount of information and considered opinion contained in their texts. However--and this is the only misgiving I have about the volume--given the two quite different artists and the number of quite different scholarly concerns, no sense of a coherent development or of an evolving artistic trajectory emerges for either of the artists, at least not upon first reading. But I suppose this is a necessary result of a collective effort aimed at two very unique artists, and it is no doubt compensated by the copious new material brought to light. There are a number of new datings, new attributions, and even new interpretations, some of these based on the increased legibility afforded by restorations undertaken for this exhibition (for example, one can now better understand Vasari's enthusiasm for Pontormo's "Pucci Altarpiece" in Florence's San Michele Visdomini, after the removal of accreted layers of grime and varnish, and the superbly subtle painting of St. Elizabeth's aging face and neck in his "Visitation" from 1528-9 (the cover illustration is a detail) reveals a naturalist impulse that had been obscured by generations of accumulated dirt. In fact, restoration and reevaluation have led in several instances to a more certain identification of paintings mentioned in Vasari's "Lives." (One of the things that emerges, a bit surprisingly, is the extent to which Vasari's information and opinions, especially in the second edition of 1568, are still so fundamental in the discussions of these works.) All this impressive scholarship is in the service of the ninety-five reproductions of the exhibited items, all but a few pages of prints reproduced full-page and in very fine color. All the mediums in which the artists worked are represented, i.e., pen and ink and washes of various colors, red and black chalk, oil on various supports, fresco, etc., and there is also a selection of engravings made after their originals. Each work is discussed at length by one of the commentators, a group including several more names familiar from Renaissance studies (David Franklin, Elena Capretti, Antonio Geremicca, and others), and is annotated with full curatorial data and a specialized bibliography. These are beautifully printed reproductions of major works, and they are supplemented by 129 comparison images, mostly full-page or half-page, with some one-third or one-quarter page in size. The frequent detail blow-ups functioning as section frontispieces contribute to making this a very handsomely illustrated volume. Its scholarly value is unmistakable, and in that respect it is a great pity that there is not more supportive apparatus. There is a very good selected bibliography, and one does not miss an exhibition checklist or capsule biographies, but in a volume like this, the absence of any kind of index is a terrible omission for the reader (and a false economy for the publisher), as it severely compromises the book's usefulness as a reference tool. In any case, the catalogue is a major achievement in both text and illustration and is likely to remain the standard work on Rosso and Pontormo for some time to come. Highly recommended.